A model for alienated bodies

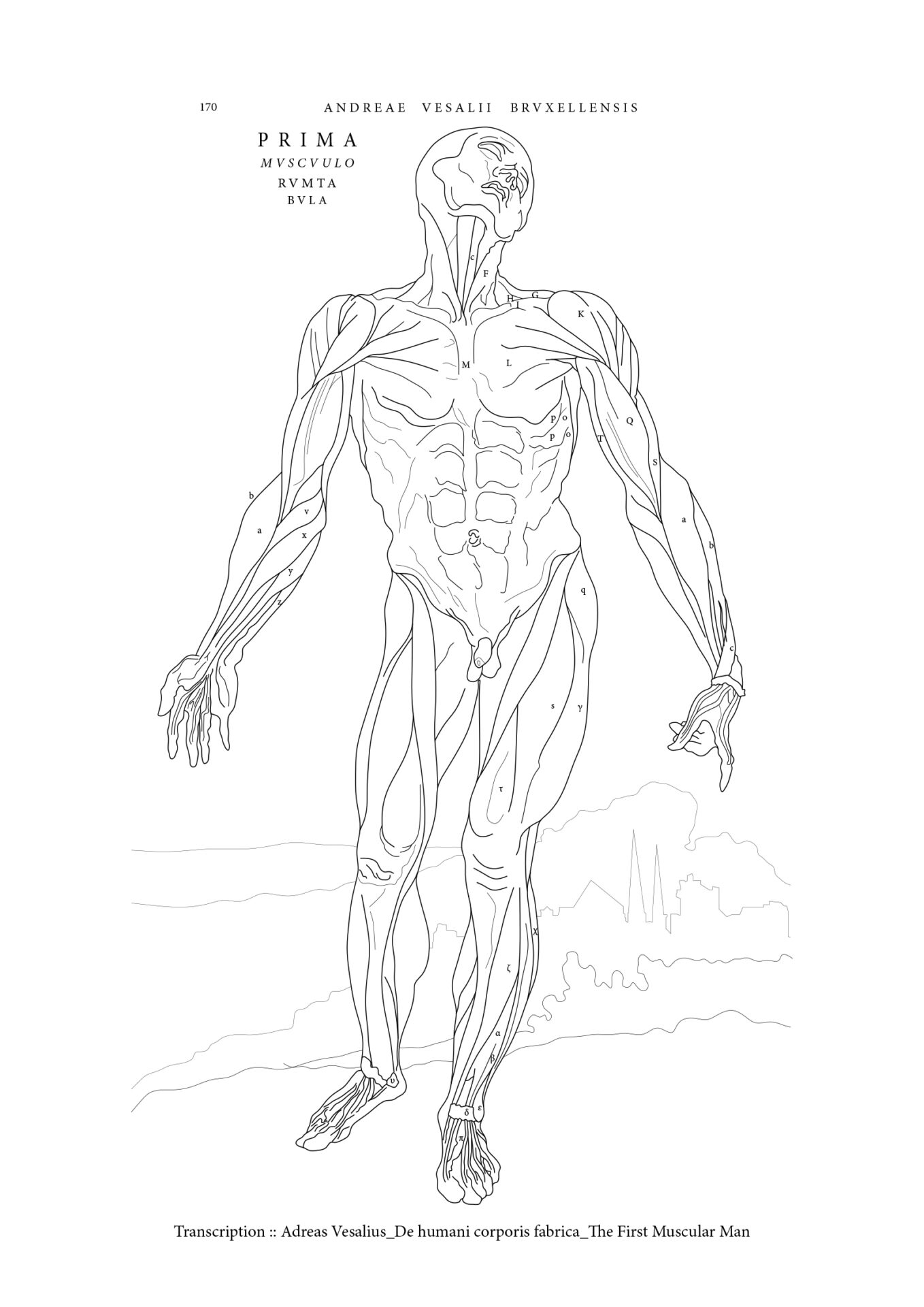

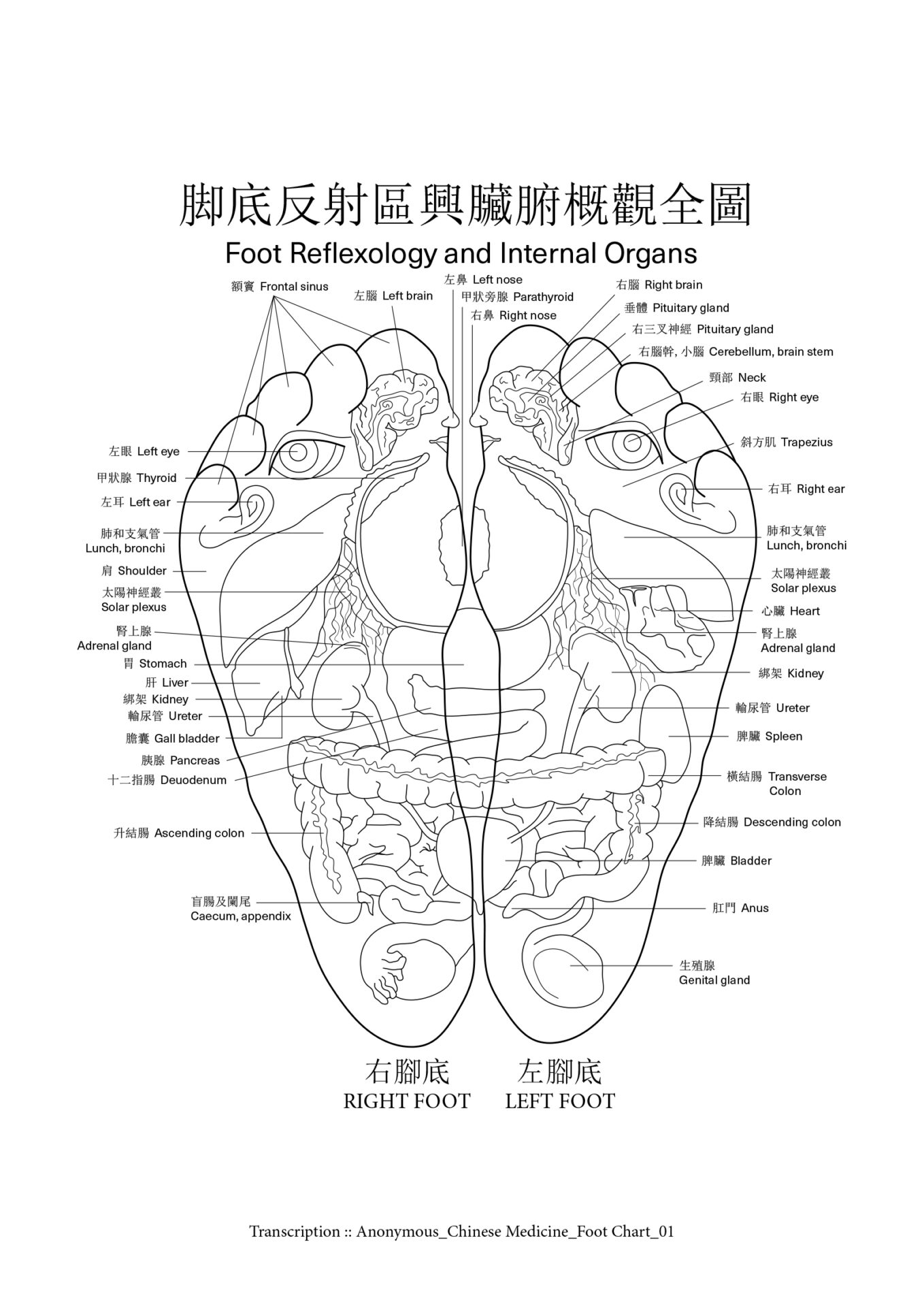

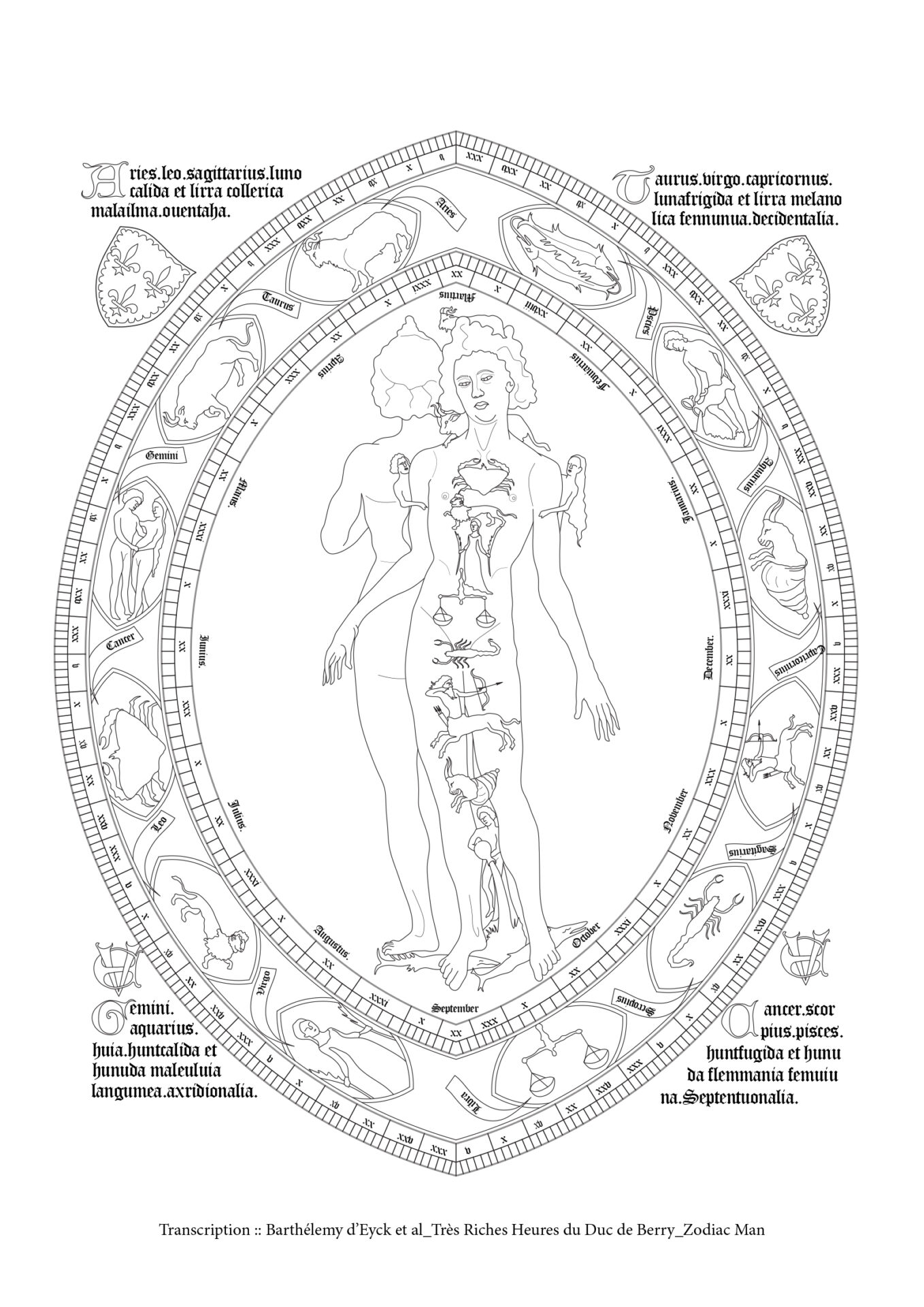

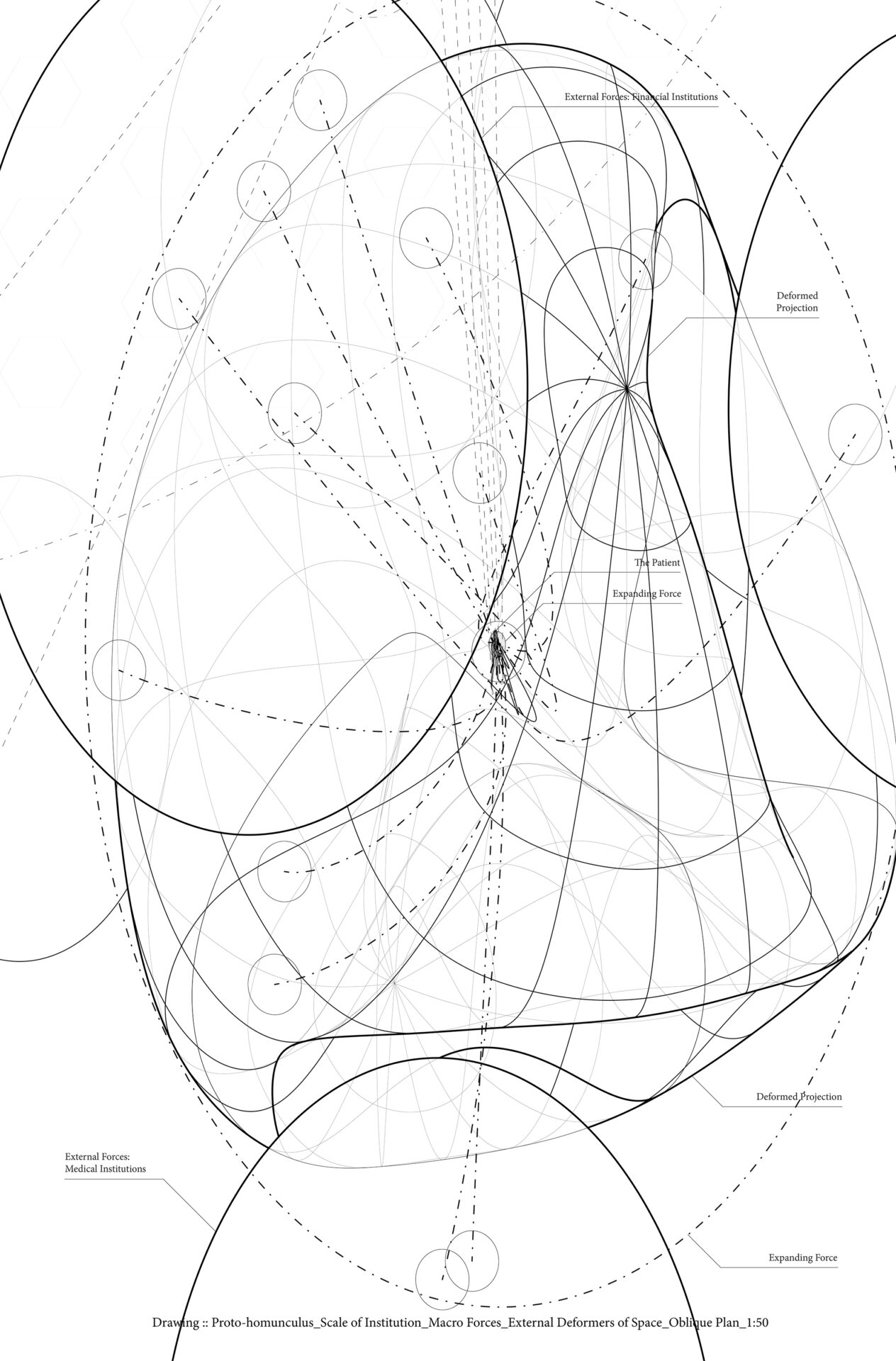

In architectural representation, bodily figurations often play only a secondary role towards its generative capacity. Whether by anthropometry or the dreaded ‘concept’, architecture seems only able to wield the body as a founding metaphor. This metaphor can only ever deal with a platonic body—it relies on its idealisation, its simplification. Yet the bodies we find all around are complicated, alienated even, and we find no body more complicated than that of a body of cancer, itself architectural in its predilection for scale, space, and metaphor. This thesis takes the position that for bodily figurations to be truly generative towards an architectural production, these bodies must be, rather than ghosts, homunculi—fully formed and complicated. I begin by attempting to excavate a model for alienated bodies, one that replaces the ghost in the drawing with a homunculus and all her complications.

Between body and bedroom

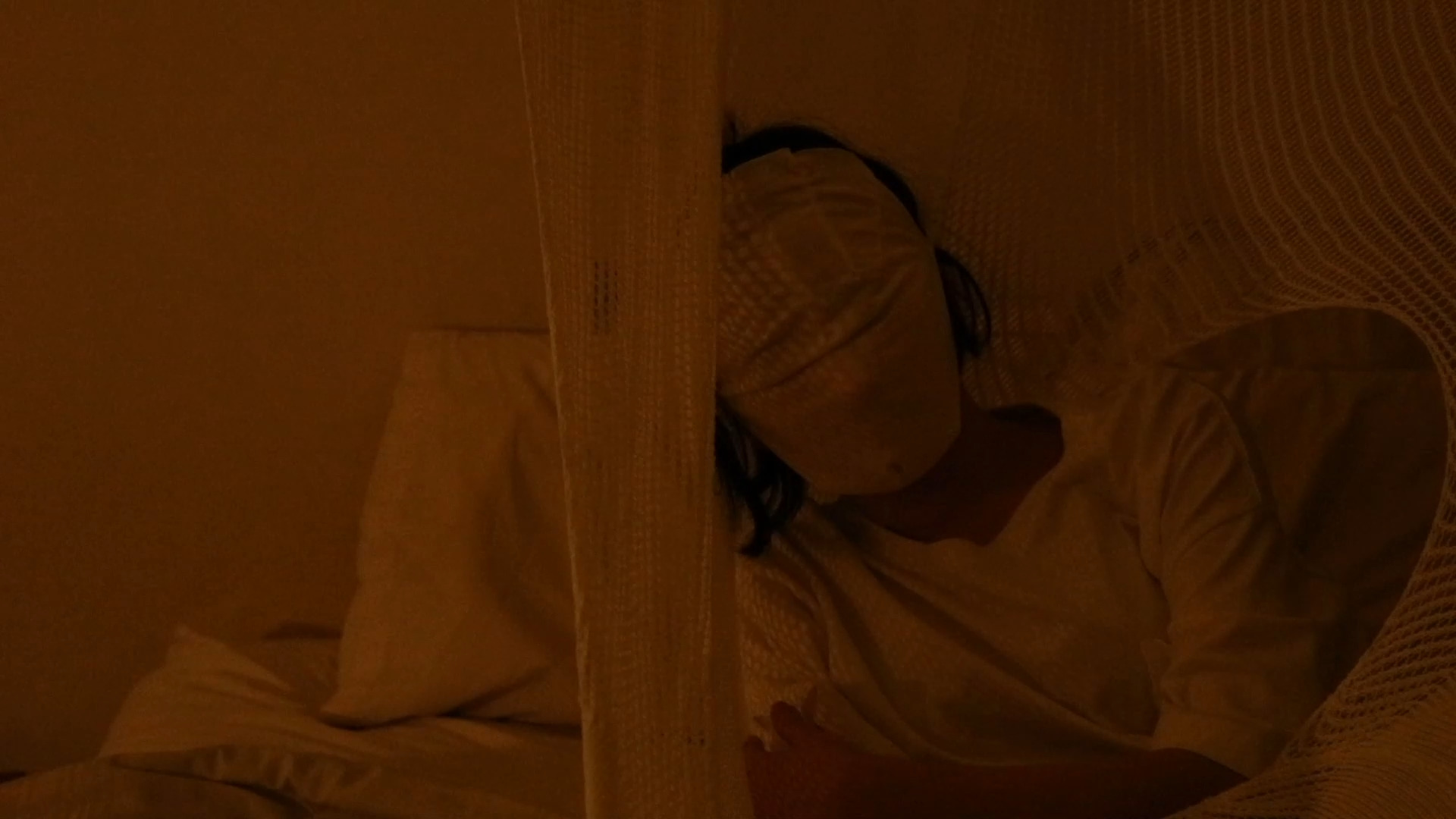

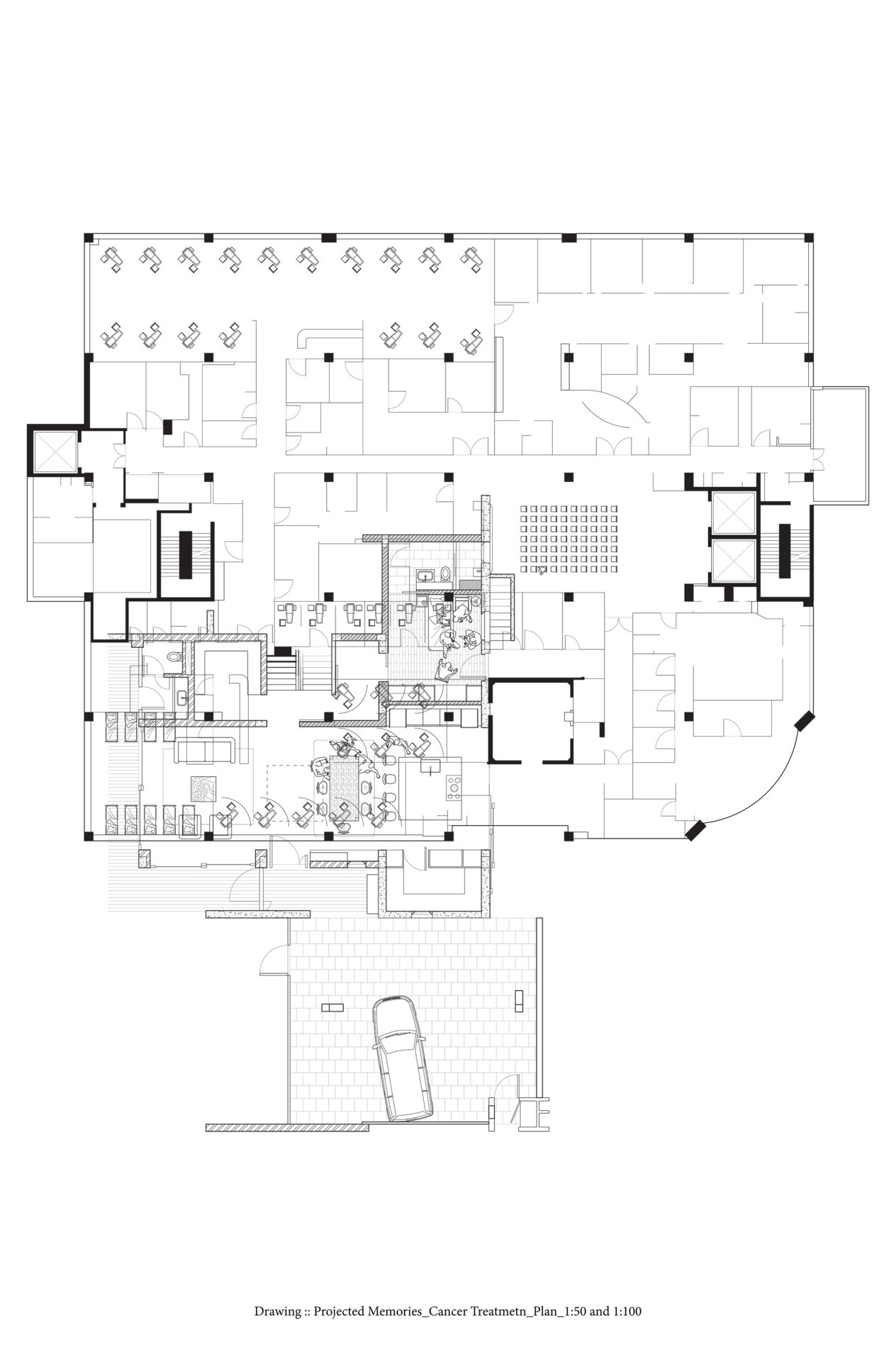

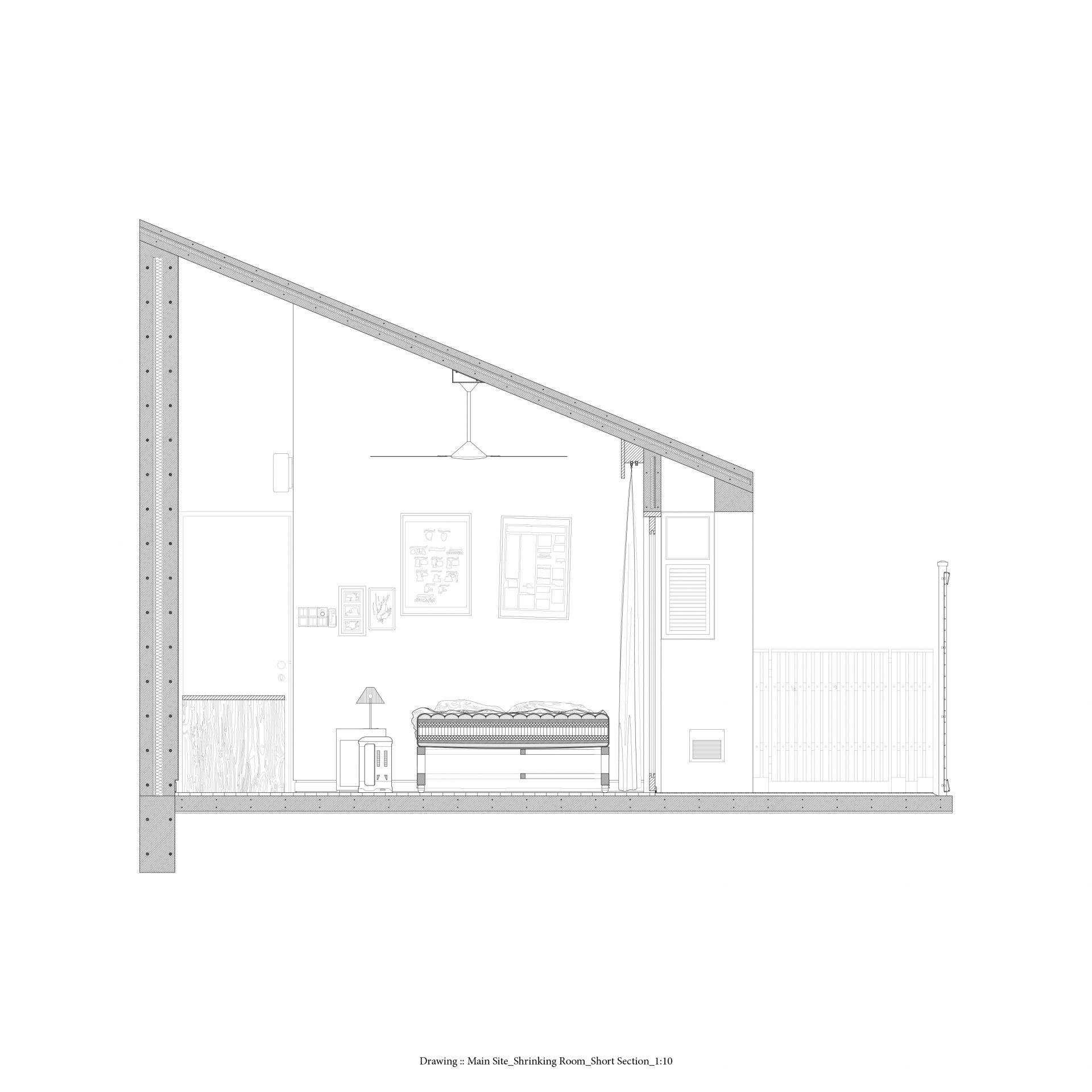

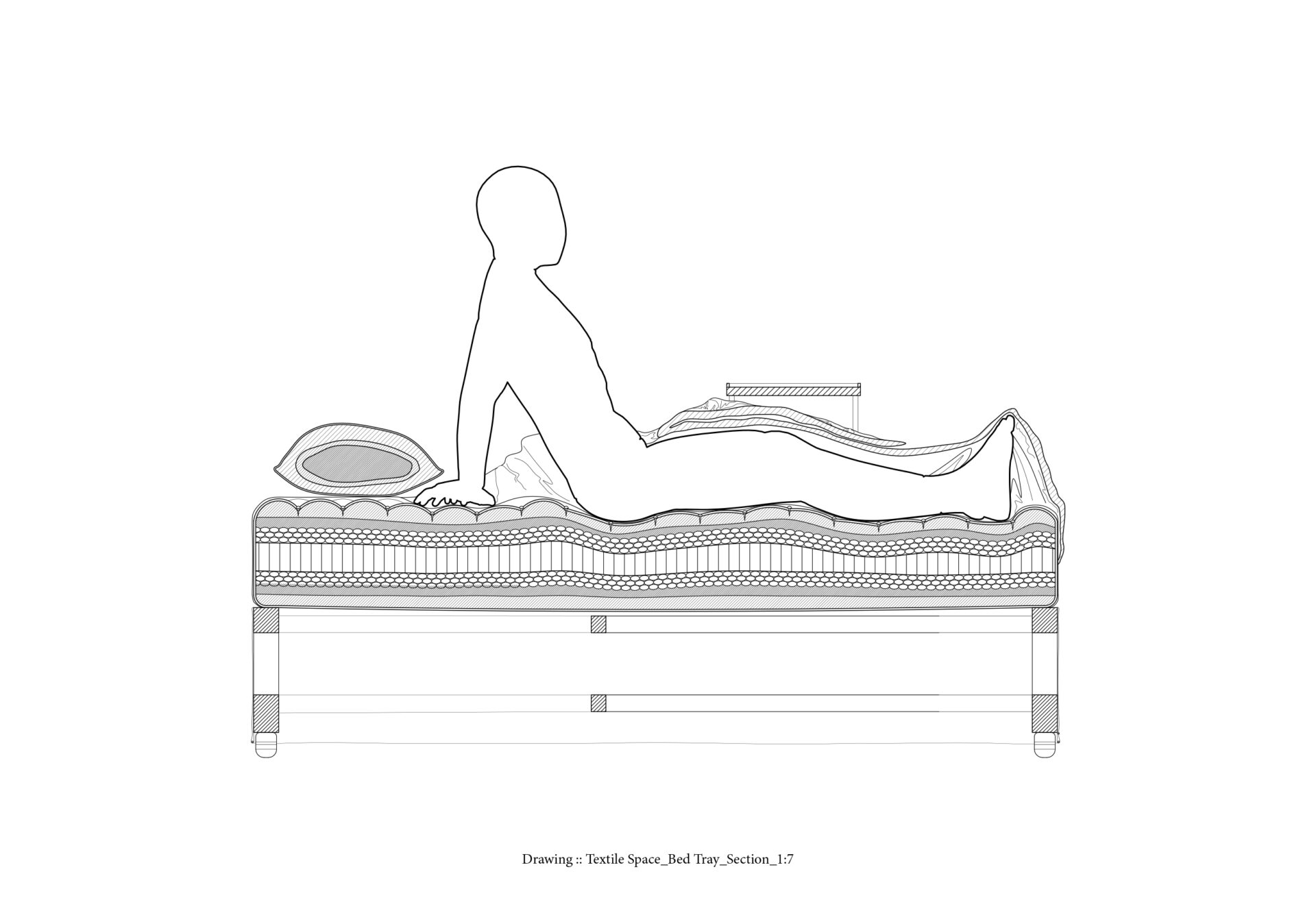

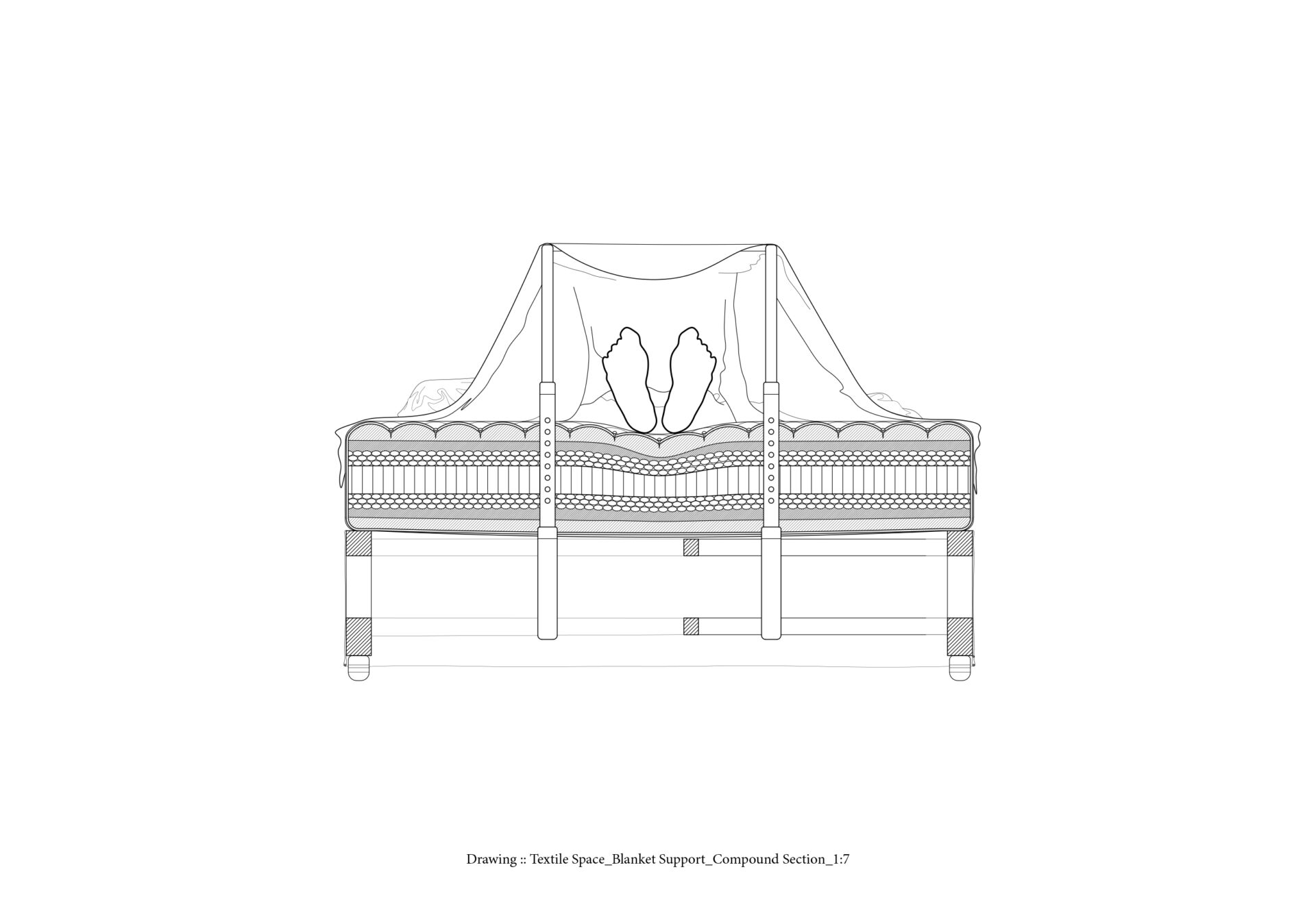

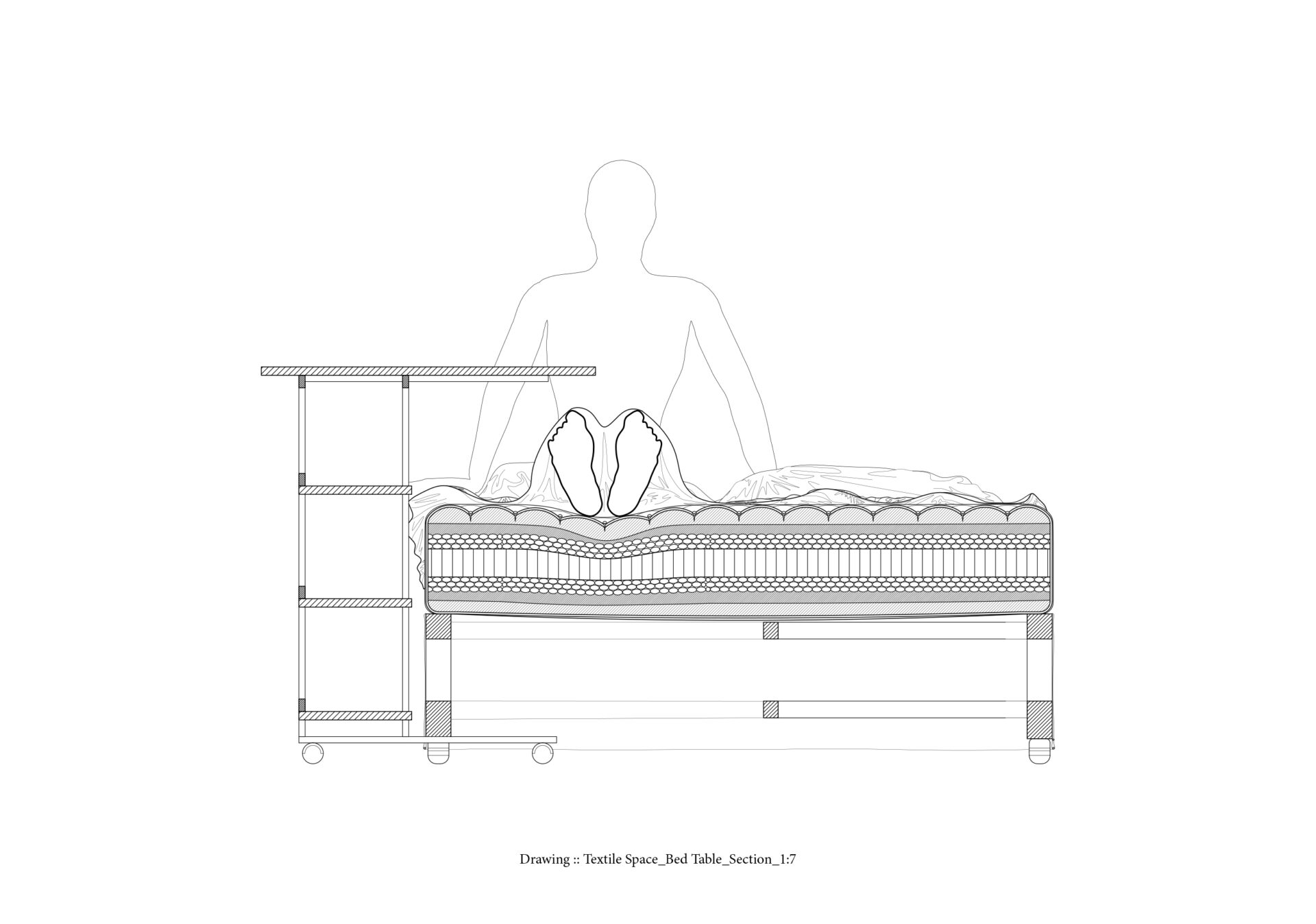

Through this model, I understand cancer to be a condition that expresses itself at multiple scales from cell to capital. Control is wrestled away from the patient, diverted towards foreign agents both internal and external to the organistic body. And this takes place in all manner of building, hospitals, care centres, homes. Here architecture seems to only be the theatre for her suffering. I ask then: is there an architecture able to provide comfort? Is there architecture that can anchor a patient through pain that is both physiological and psychological? The solution I ruminate over in this thesis is an intervention in a domestic typology of a simple bedroom, part programme for respite and part programme for treatment—a once safe space turned hostile. It is a scale that sits between body and bedroom where I ask if an architecture can fulfil the promises it makes to the betterment of the body and its ability to act, if indeed it were contingent upon a model for alienated bodies.

Last Knit

The result of this research is a new kind of wall, presented as an odyssey through representation, technics, and making. These walls are a typologically ambiguous intervention that appears to resemble an enclosure, a hammock, a garment, and none of the above all at once. As the patient exerts force over these walls, they warp in a way that is distinct to the patient who sees the grain of the fabric distort against the weight of her body. She is not separate from the space within which she resides, but one with it as a kind of prosthesis for care and living. This is a kind of architecture that is itself alienated against our prejudices against things that lack solid and unmoving form, against the beguiling allure of concrete masses. This architecture, like the body it serves in this thesis, cannot be alienated any longer in a world where we are all subject to greater forms of alienation. If we are to do anything about this contemporary condition that will only grow more severe, we must be willing to delimit the ways we do architecture.

Supervisor's comments:

Proposing The Cancer Homunculus as an alternative model of a person that has been distorted (alienated) through cancer, Sam probes right at the heart of how we make “architecture” for “people.” The investigation covers an enormous range, covering many dialectical concepts: that of the idealized objective body versus the imperfect subjective one, representation versus reality, architecture versus the domestic space, hard immovable materials versus pliant changeable ones, architectural construction versus knitting, et cetera. The resultant project, of a bedroom installation intended to “give comfort” to a cancer patient, belies a daring re-frame of the contexts and constructs within which architects design.

- Assoc. Prof. Ong Ker Shing