Summary

This thesis originated from an investigation of assemblages in informal cardboard collecting – and culminated in the study of how such material assemblages gradually reconstituted themselves across different and larger scales. Expressed architecturally as a recycling centre, the thesis seeks new emancipatory findings and possibilities for man, architecture and informal recycling work through object-oriented perspectives.

Specifically, studying how these objects exist, aggregate and affect the body across different scales yields new understandings and approaches to architecture as a mediator between body and object. It suggests a direction to look at architecture from the material itself first, rather than asking first how it serves us. How we manouevre the space quickly becomes a question of how the material conditions the body, and how the body responds to preserve itself.

Initial Research – Small-scale Assemblages

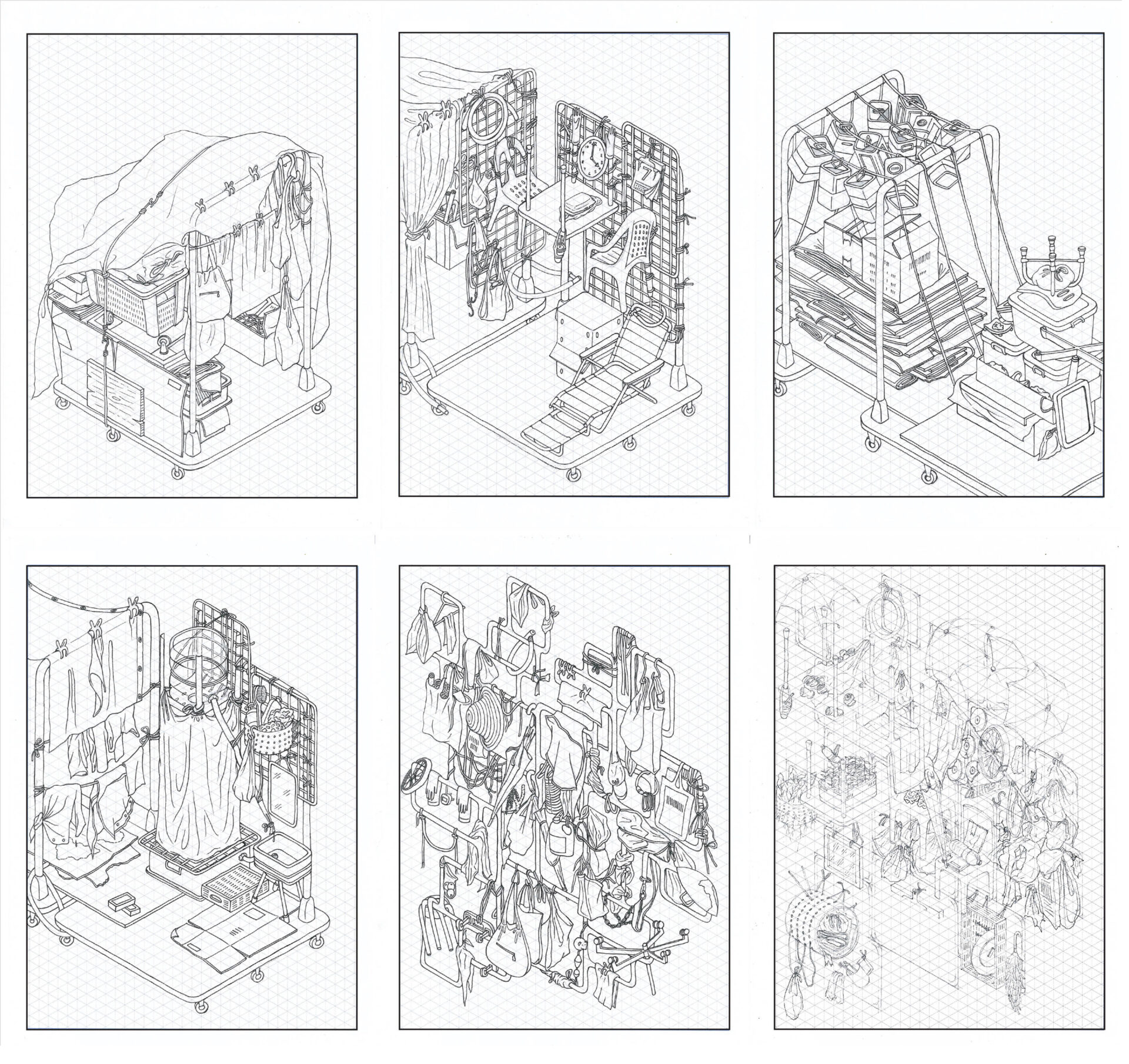

The initial research approach adopted was a close observation and drawing study of material assemblages found in the low-income landscape of Toa Payoh (where I live and where I have found cardboard collectors’ carts scattered around).

The studies reveal that the different facets of the low-income demographic are intrinsically intertwined, and these blurred boundaries are manifest in the material culture of their objects. They tell of a set of personal belongings for living and working that are all found in the public sphere, forming a “diaspora” of objects in the low-income landscape that are constantly deterritorialized and re-territorialized, never truly belonging anywhere.

By conforming the chaos of objects in the environment to the operational method of the isometric grid, these seemingly random and disordered assemblages begin to reveal a hidden logic and intelligence – with a very methodical processing of various materials found in urban space, and telling of various inner workings of their psyche.

Medium and Large-scale Assemblages

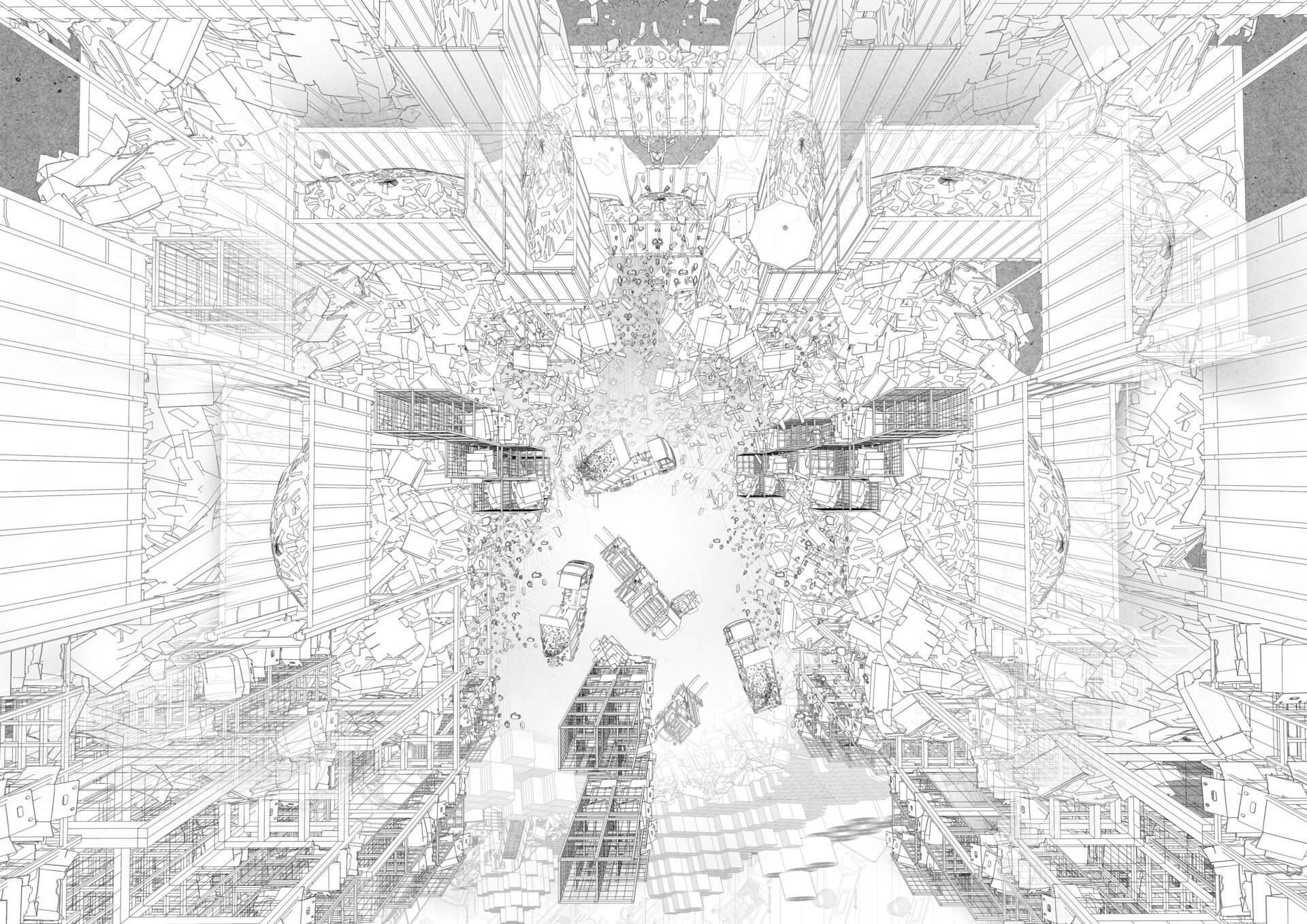

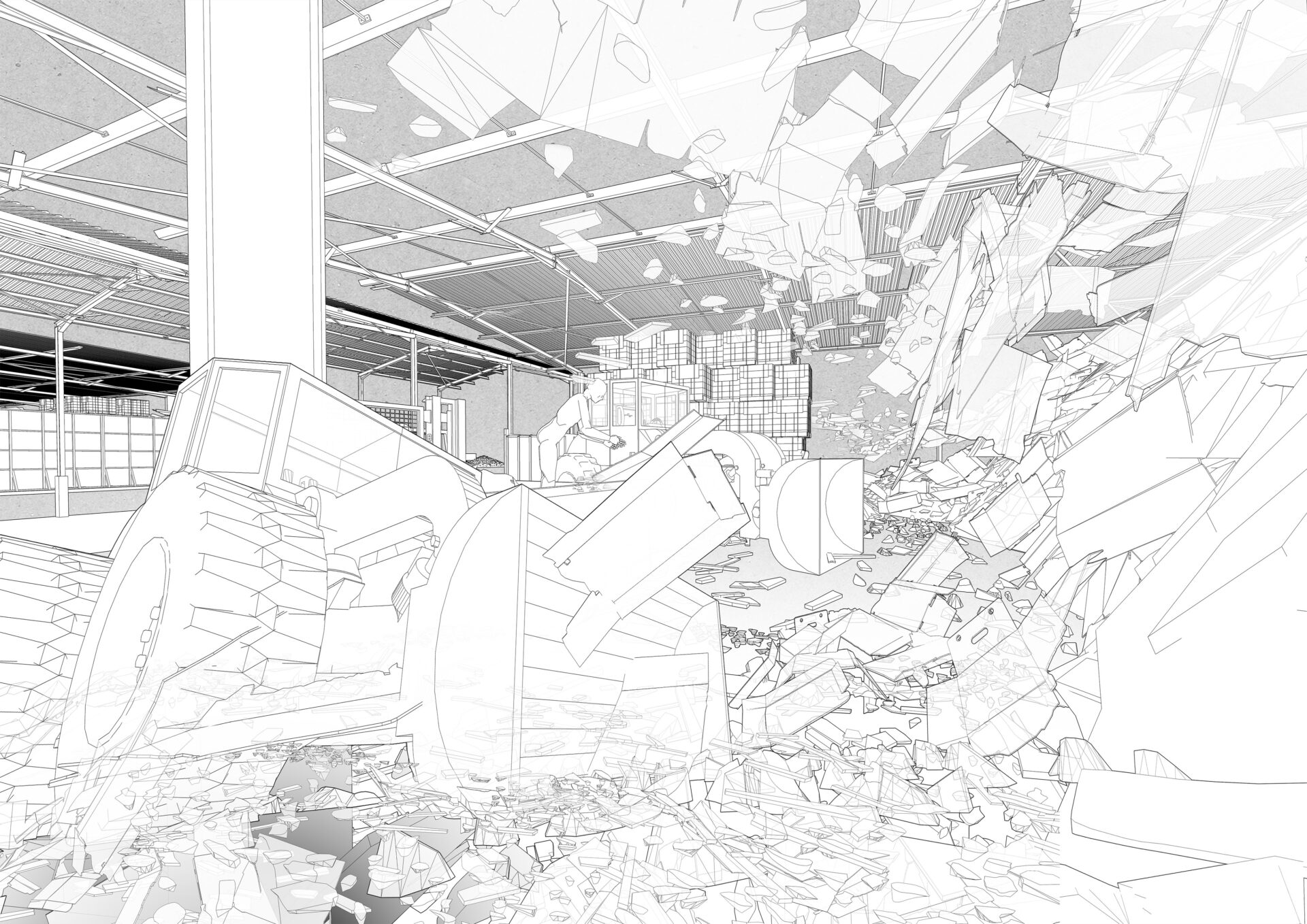

The next part consists of drawing experiments based on the notion that the earlier research drawings dealt with small-scale assemblages, and that its manifestations across increasingly larger scales are worthy of further study – in order to understand how the materials exist, aggregate and affect the body across different scales.

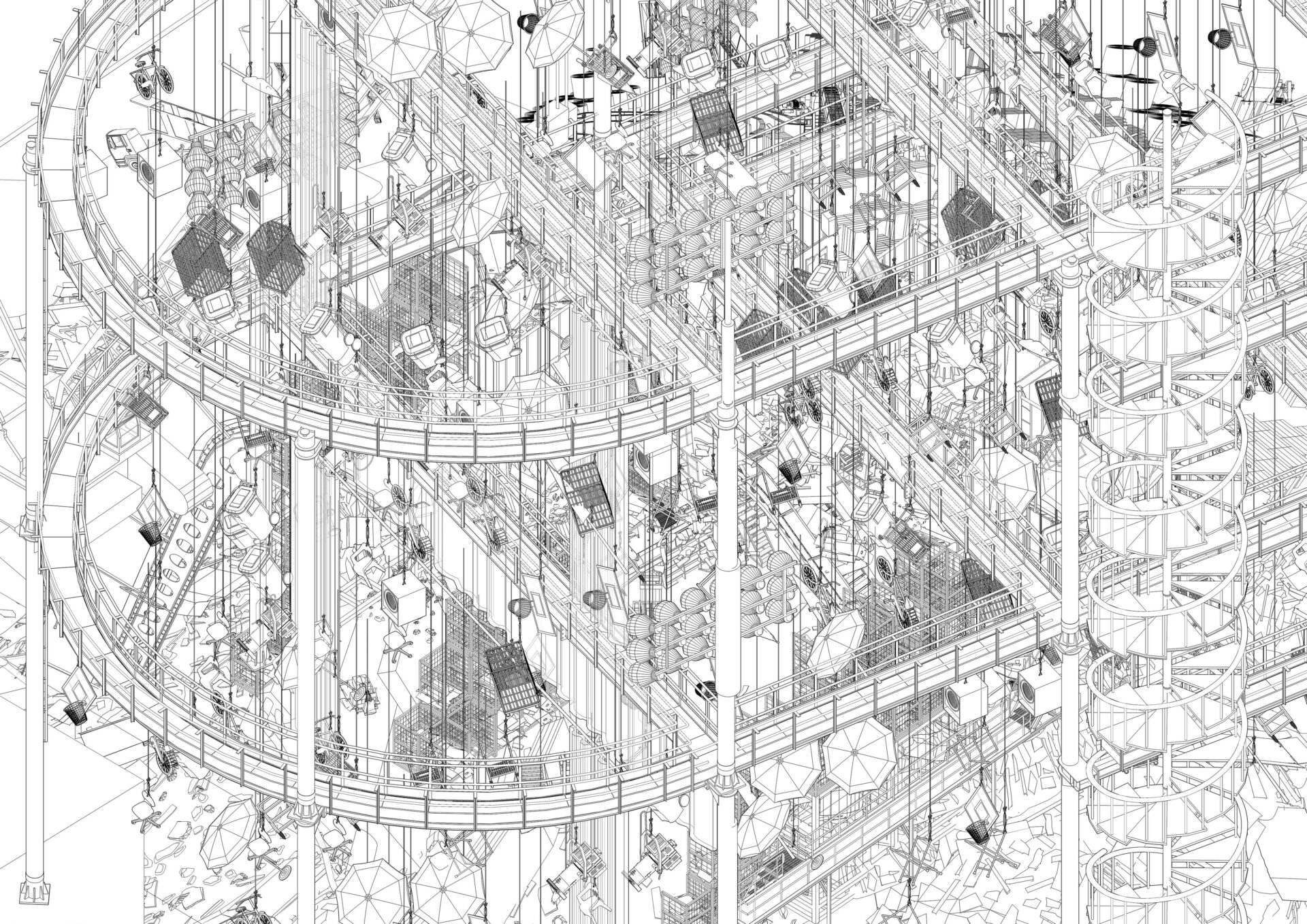

The medium-scale assemblage drawing experiment revolves around the premise that the earlier sketches are “dried sponges” that can be “rehydrated” – analyzed for architectural opportunities and expanded.

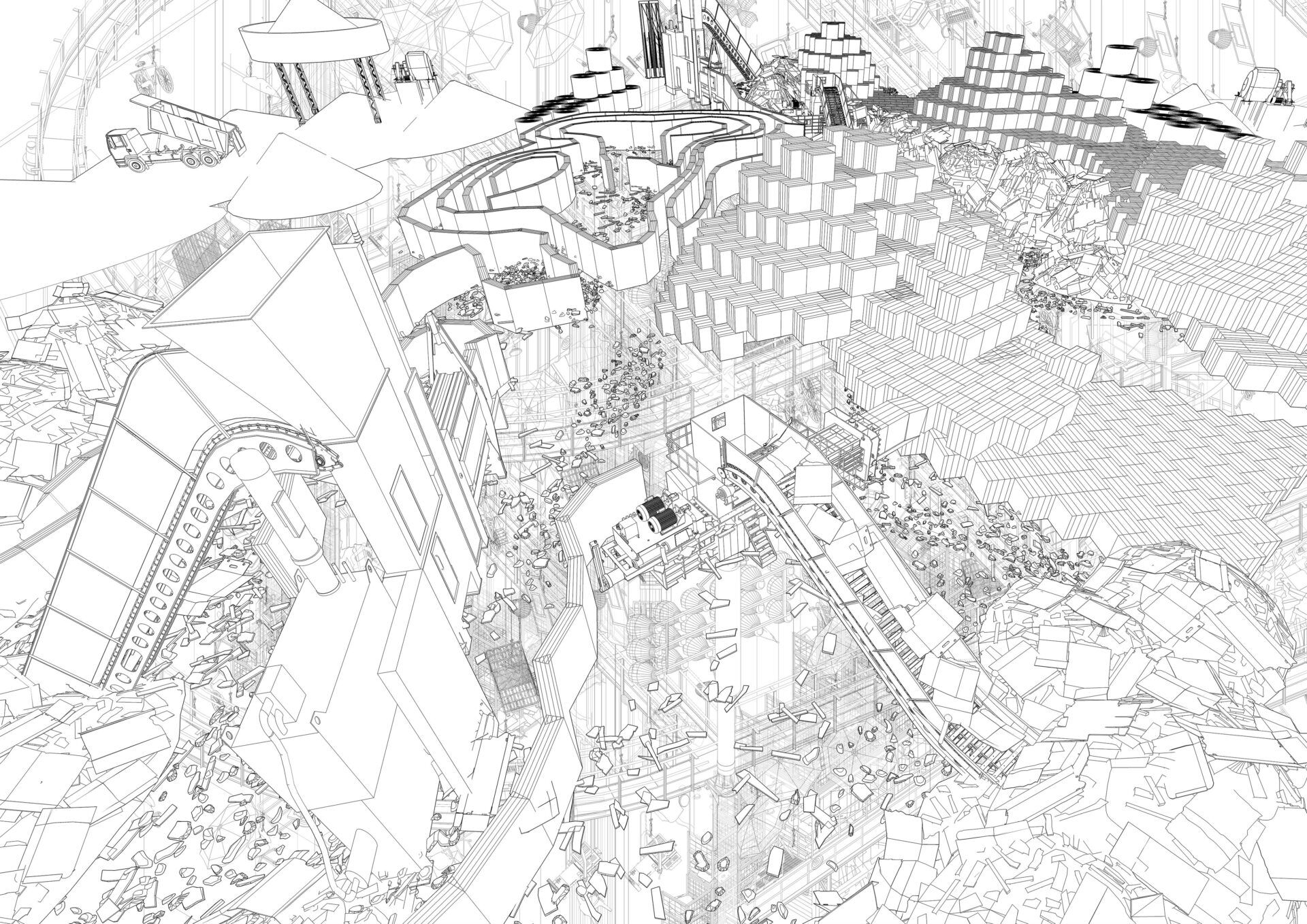

The subsequent L-scale experimental drawings explore the phases and limits of material aggregation and its affect on us.

Architectural Translation

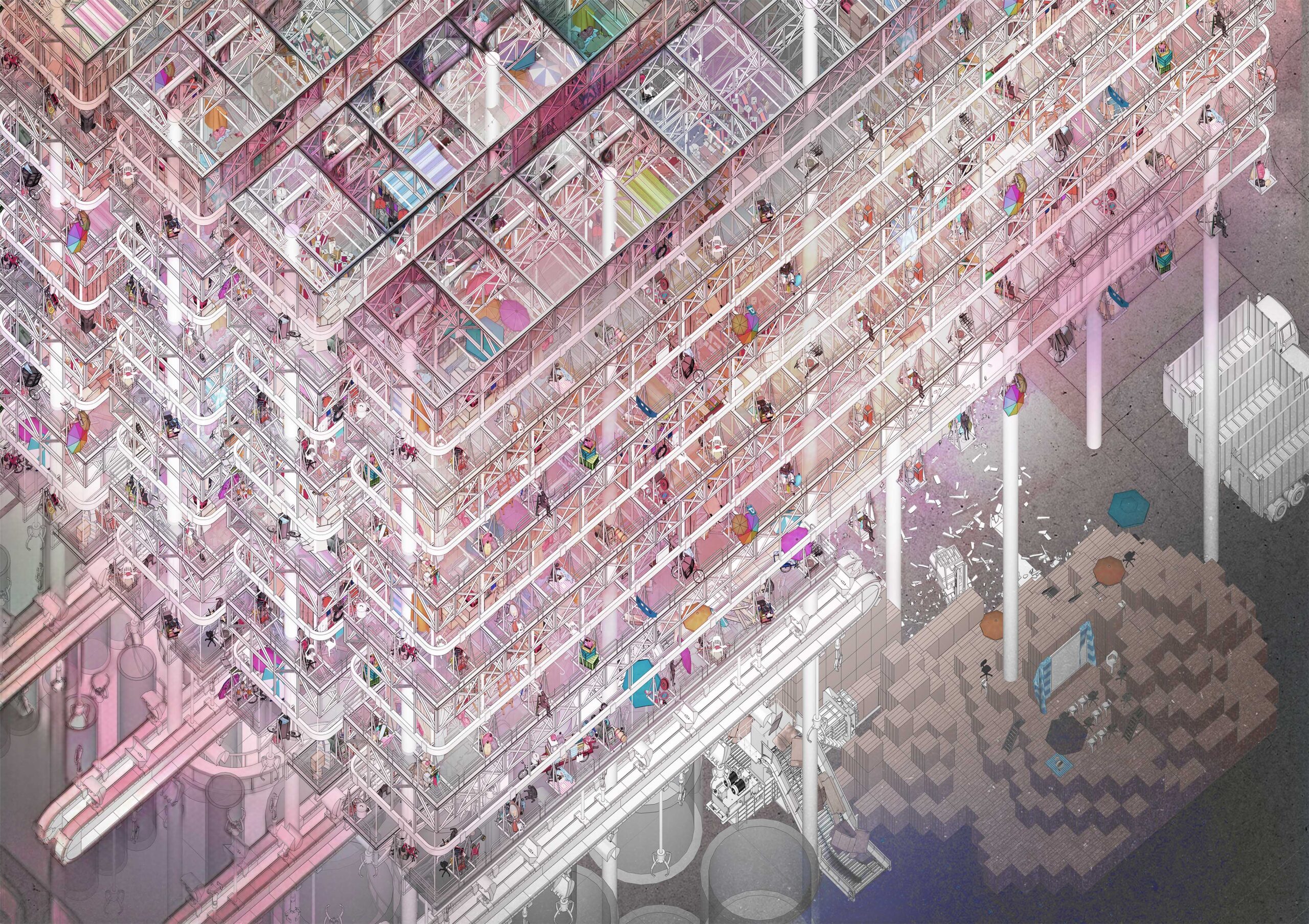

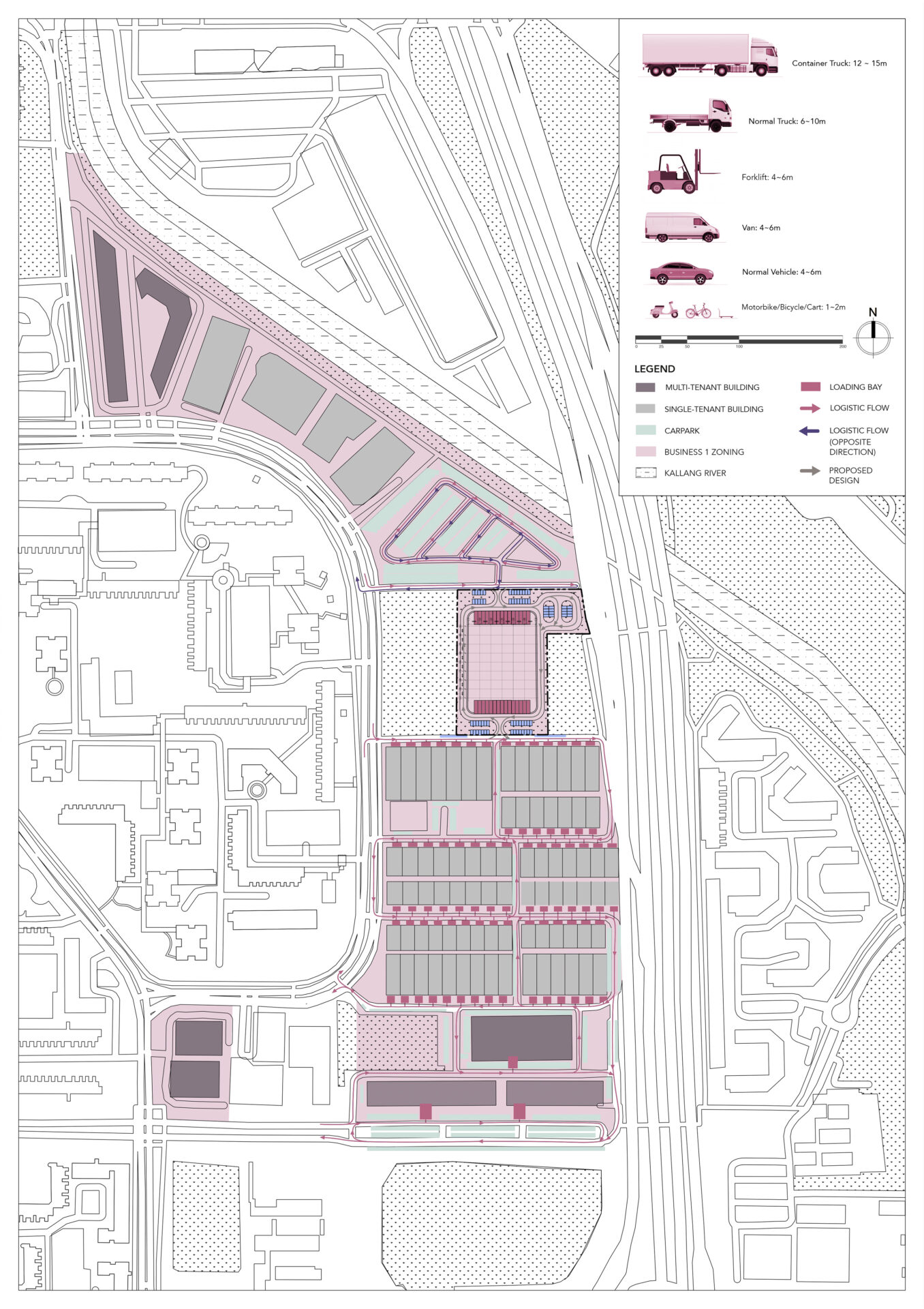

This is the context in which I wished to culminate my research into an architectural design approach: conceiving of recycling infrastructure as a big “field “ where all kinds of recycling activities and assemblages could be generated – in their own heterogeneous, pluralistic, and potentially self-organizing ways.

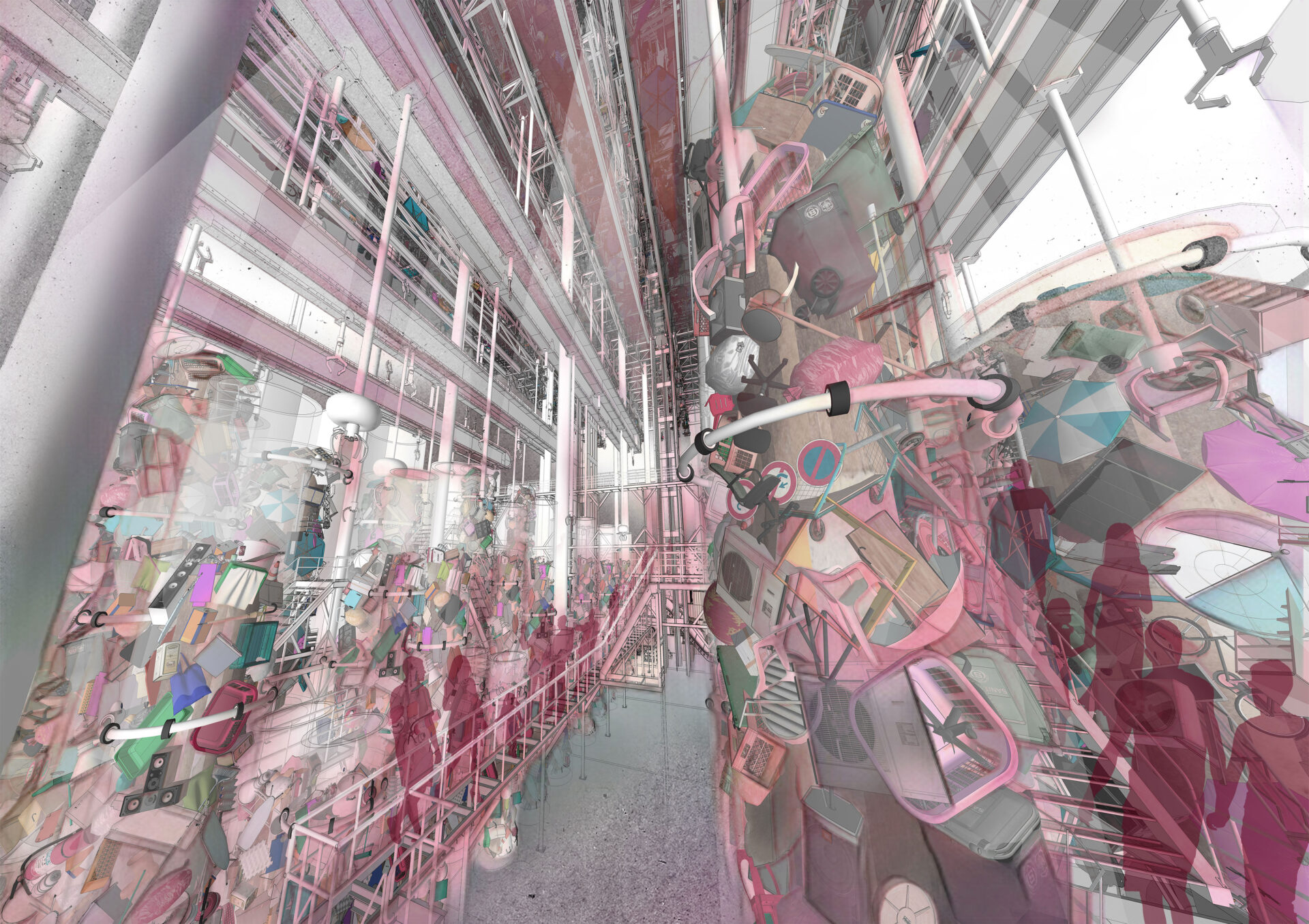

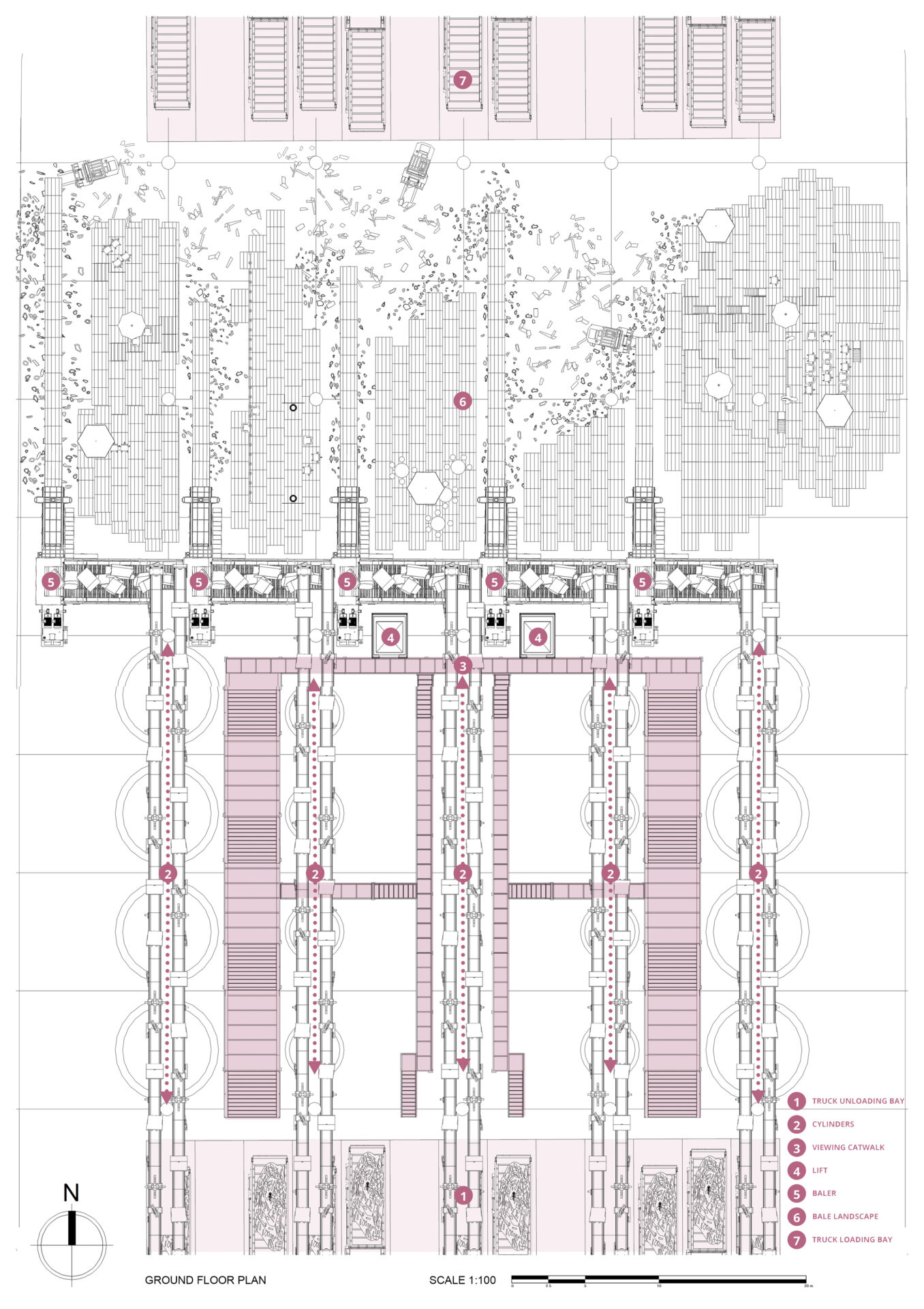

Beginning from the unloading bay, trucks unload items at different bays where UFO claws put them into cylinders of various sizes (different bays are for different-sized items and cylinders). A procession of waste pilgrims enter this temple-like space to shop around the cylinders. The cylinders are scanned for the material that shoppers want, and grabbed with the claw to be brought upstairs to the platform level for collection.

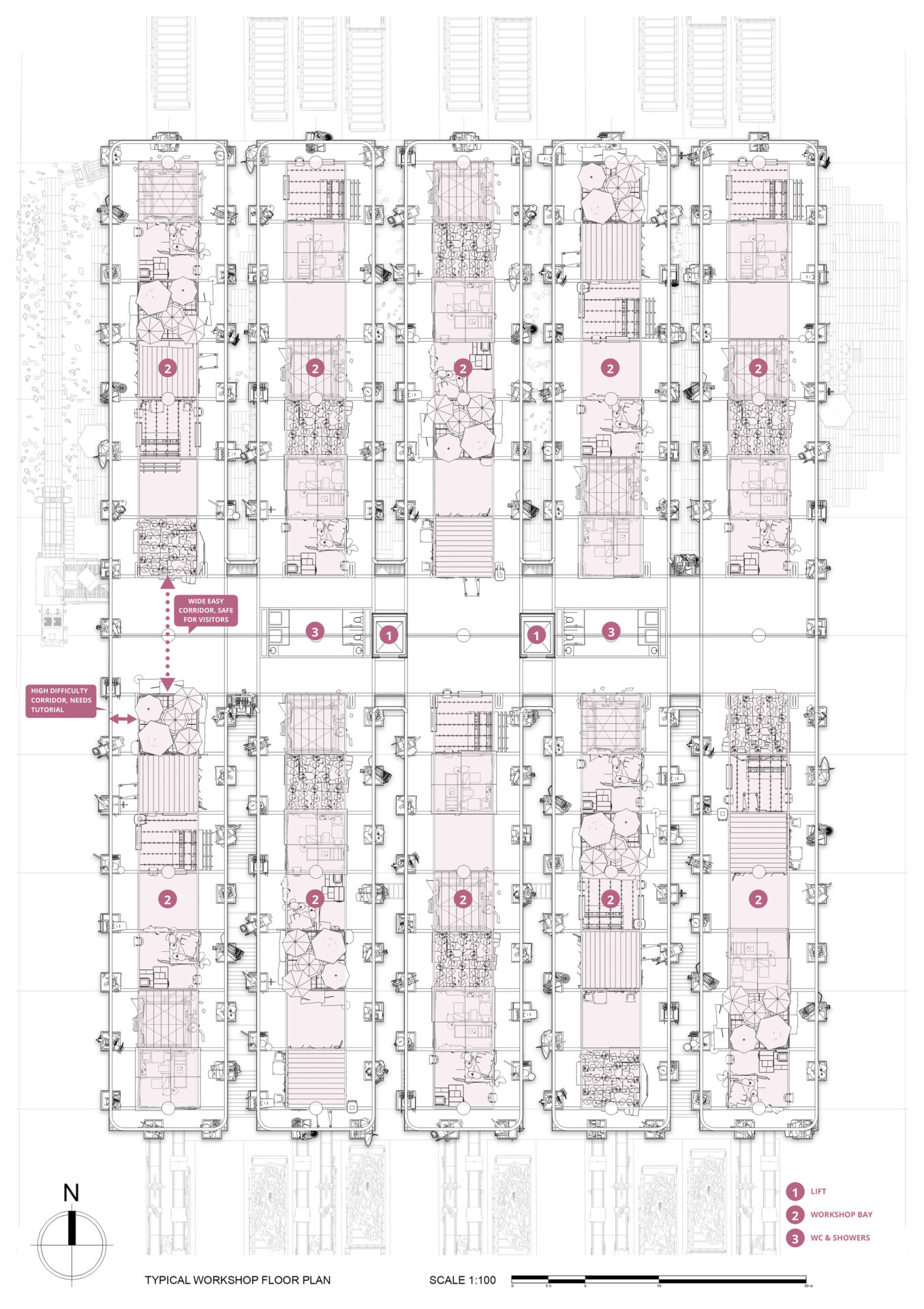

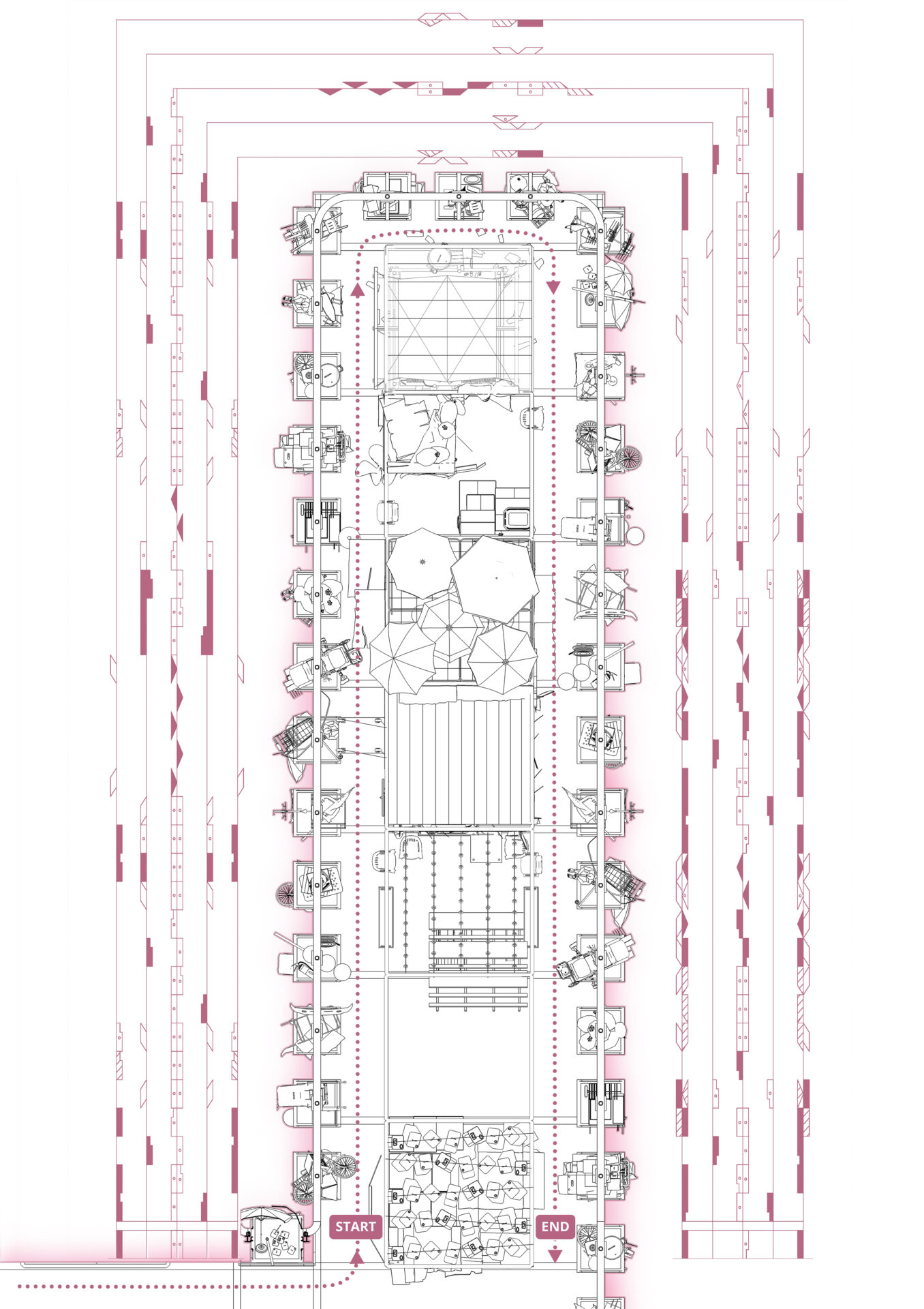

Recyclers on the platform level work with workshops above to pick up the materials they need, and send them up on a conveyor that circulates the whole building. The conveyor circulates material across the building for workshops to pick up and form their own specialized repair and crafting spaces. Lastly, a dance has to be learned by visitors who shop around the workshops so they know how to navigate around the spaces and moving objects.

Therefore, by countering the anthropocentric gaze in design to embrace the rich, independent (and codependent) workings of extrinsic material relationships found in our surroundings, one is suggested to first look at architecture from the perspective of the material itself, rather than asking first how it could serve us. How we manouevre the space quickly becomes a question of how the material conditions the body, and how the body responds to preserve itself.

This is evidenced in the dance that has to be taught and learnt in order to navigate the workshop bay areas, as the body is forced to negotiate itself with the changing landscape of materials running along the conveyor and the workshops. In that sense, the transformation of architecture could occur as such:

“[Architecture’s] instrumentality can be reconceived… as the site of architecture’s contact with the complexity of the real. By immersing architecture in the world of things, it becomes possible to produce… a ‘volatile, unordered, unpoliceable communication that will always outwit the judicial domination of language.’”

– Evans, R. (1995). The Projective Cast. MIT Press. discussed in Allen, S. (1999). Points + lines: diagrams and projects for the city. Princeton Architectural Press.

This dangerous waltz between man and object forms the ultimate violent confrontation of the human being and the extrinsic world of objects, of which this architecture seeks to establish a stage for.

View thesis report here and view portfolio here.

Supervisor's comments:

The Material Field envisions an alternative relationship between human being and objects. Founded by a close investigation of informal cardboard collectors’ improvisations in Singapore, the project proposed a complex of a recycle facility and studios for “makers” who intercept and take advantage of the recycling materials. On one hand, the field provide a great opportunity for makers to enjoy improvisational creativity, while on the other hand, x-ray technology and a conveyer system controlled by digital media with deep-learning capability start to consume such creativity, and subsume the makers to an object under control. Within this field where materials are seemingly liberated and makers are happy, the irony is expressed in a subtle and comical manner: the question is who governs the entire field.

- Assoc. Prof. Tsuto Sakamoto